Capturing Grace and Dancing Through the Pain of Parkinson’s Disease

Written by Laura Dattaro

Some days, the stars of David Iverson’s documentary Capturing Grace can’t walk, or tie their shoes. But over the course of a year, they show up to a studio in Brooklyn and dance, learning choreography and improvisation to prepare for their first public performance.

If it weren’t for the fact that all of the dancers in Capturing Grace have Parkinson’s Disease, they might not have much in common. Among the group is a social worker, an AT&T executive, a poet, an athlete and exercise science professor, and a bank manager. They’re different ages and live in different parts of the city; their disease affects them in different ways.

But none of them had ever danced before joining the workshop, which is taught by two dancers from the New York-based Mark Morris Dance Group. “They’ve each had something go missing,” Iverson says in his voice-over narration that opens the film, describing how some have tremors, some have an arm that doesn’t swing when they walk, some can no longer smile. “But the dream to move freely never goes away.”

Leventhal helps the dancers realize that dream by teaching them to dance, a feat that seems to be more difficult for the dancers some days than others. But while Parkinson’s currently has no cure, new science is showing that movement and exercise can be helpful in managing the disease, a point that seems to be proven in the movie.

During an interview at her home, Cyndy Gilbertson is barely able to sit still in a chair and demonstrates to the filmmakers how her walking is stiff and difficult, marked by short steps and tremors in her arm. When she turns on music, though, and begins to dance, she moves around the room with purpose and fluidity, her muscles holding steady and her arms free of shaking. “There’s a joy that I get from moving around,” she says, echoing what fellow dancer and Parkinson’s patient Judy Rosenblatt describes earlier in the film as the ability to “to fly in an organized pattern.”

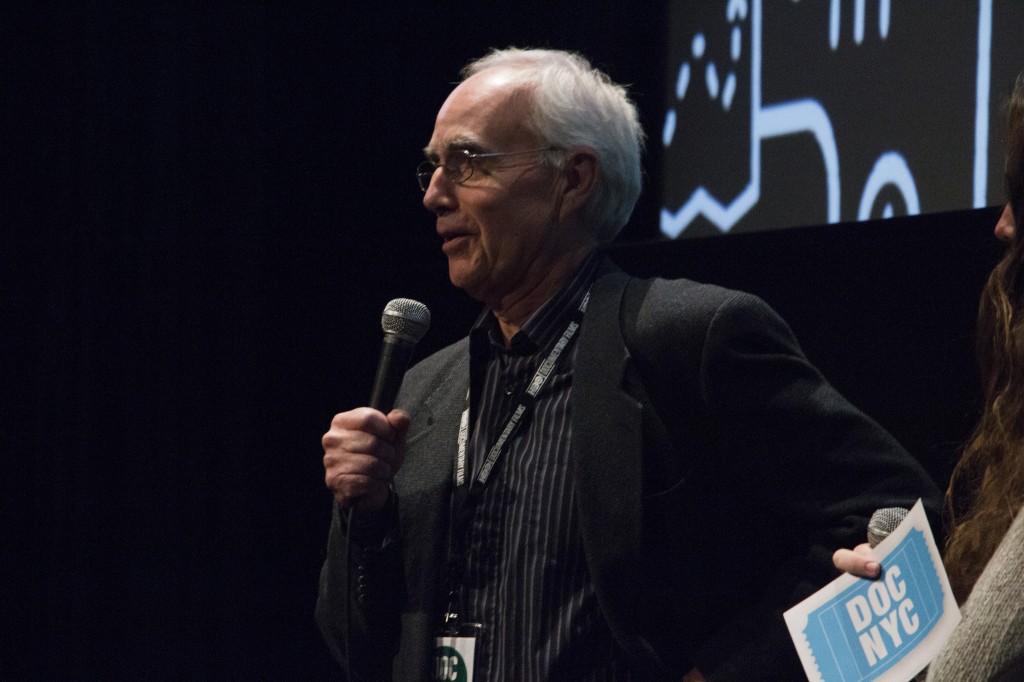

Iverson, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2004, first discovered the workshop when making a PBS film about his own family’s story called My Father, My Brother, and Me. “When I saw the class, I just knew that it was something I wanted to come back to,” Iverson said in a discussion following the screening. “When you know something’s a good story, you stay with that.”

After the Thursday evening screening on the last day of the Fifth Annual DOC NYC Festival, Iverson was surrounded on stage by all the dancers from the film — save one, Reggie Butts, who passed away five months after the group’s first performance. Reggie seemed to face the most serious health ailments during the film, eventually suffering an aneurysm that left him unable to perform in the final show.

Reggie’s wife performed in his place while he watched from the audience. The film closed with a quote from him, which displayed the spirit of what the group was working to accomplish: “When we dance, there are no patients,” he said. “Only dancers.”

For more about Capturing Grace, visit the film page on the DOC NYC website.

Laura Dattaro is a freelance reporter in New York City focusing on science and the environment. Follow her on Twitter @ldattaro